West End Jazz

Posted on March 14, 2012 – 2:59 PM | by William Burg

By William Burg

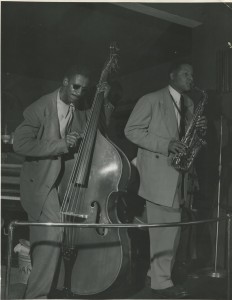

Photos courtesy of Keith Burns

In the 1940s, Sacramento’s West End was filled with the sounds of jazz. Based around M Street (renamed Capitol Avenue by 1940), the neighborhood was radically changed by the start of World War II, the forced relocation of Sacramento’s thousands of Japanese Americans to internment camps, and a migration of African Americans to Sacramento. Many of these migrants came from the Southern states for jobs in Sacramento’s railroad shops and canneries, or at nearby airfields and Army bases. Some purchased businesses from the departing Japanese, opening a variety of businesses, but the best known were the jazz clubs. These clubs became so popular they crossed racial barriers and made Sacramento a stop on the touring circuit for the greatest jazz musicians of the 20th century.

Sacramento already had jazz clubs dating back to the ragtime era. Ancil Hoffman’s saloons and restaurants dominated K Street through the 1920s, and Japantown had its own jazz bands and venues dominated by the “Night Hawks” and the M Street Café. The African American owned Eureka Club on 4th and K was considered one of the biggest nightclubs in northern California, reputable enough for inclusion in a Sacramento guidebook aimed at tourists attending the 1939 California Centennial. But racial lines were difficult to cross in Sacramento, even if segregation was “de facto,” more by tradition than force of law. New arrivals from the South (where segregation was statute law) felt less restricted, and the 1940s saw Sacramento’s first Black doctors, morticians, policemen, attorneys and other professionals—and nightclub owners.

Louise and Isaac Anderson and William “Nitz” Jackson purchased a liquor store from a Japanese owner in 1942, and established the Zanzibar Club at 530 Capitol. The Zanzibar featured touring musicians like Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington. Local musicians like Vincent “Ted” Thompson (who owned the nearby Thompson Mortuary) also graced the Zanzibar’s stage. Across the street from the Zanzibar, the Mo-Mo Club, owned by brothers Alex and Hovey Moore, featured both dancers and musicians. Other clubs included the Congo Club, at 329 Capitol, the Cotton Club at 6th and J, and the Clayton Club at 1126 7th Street, beneath the Marshall Hotel (originally the Hotel Clayton.) The Clayton featured musicians like The Treniers, Cab Calloway, and comedian/tap dancer Gene Bell. These clubs became a major part of Sacramento’s live music scene, which included venues like Buddy Baer’s, The Tropics, and the Grand Ballroom at the Senator Hotel. Acts that outgrew the local jazz clubs played bigger shows at the Memorial Auditorium.

The widespread appeal of swing and bebop jazz drew crowds that trampled Sacramento’s color line under dancing feet. While Sacramento’s small population could not match the big-city jazz scenes of Los Angeles or San Francisco, strong attendance at West End clubs put Sacramento on the touring circuit of most major acts. In addition to regular weekend shows, the Zanzibar was best known for its informal Sunday afternoon jam sessions, free-form experiments that drew performers like Louis Armstrong and Dizzy Gillespie.

The success of the Zanzibar also brought negative attention. Challenges to Sacramento’s long-held color line met strong resistance from established white interests. Based on rumors of prostitution at the Zanzibar, state liquor officials revoked its liquor license in 1949, effectively closing the club. Some saw the revocation as retaliation by white businessmen jealous of the Zanzibar’s success. Nitz Jackson moved to southern California after the closure of the Zanzibar. The Andersons kept a nearby liquor store, A&J Liquor, relocating to Stockton Boulevard when the West End was redeveloped in the 1950s.

The redevelopment of Capitol Mall meant the end of the West End jazz clubs. Sacramento’s Chamber of Commerce had promoted conversion of M Street from a mixed-use immigrant neighborhood into a ceremonial boulevard since 1909, but federal funds for acquisition and demolition were not available until the 1950s. Changes to redevelopment law in 1954 eliminated the need to provide replacement housing for the 10,000 Sacramentans who lived in the redevelopment zone. A media campaign urged redevelopment of the West End, and its bustling clubs were characterized as “blight” by those seeking to expand Sacramento’s central business district. By the 1960s, M Street was transformed into the placid Capitol Mall we know today, and erased clubs like the Zanzibar and the Mo-Mo from downtown Sacramento and public memory. Today, as downtown Sacramento works to re-establish itself as a destination for music and nightlife, the stories of Sacramento’s jazz legacy can be shared and celebrated after decades of silence.

Tags: History, Jazz, Sacramento History, West End, William Burg

2 Trackback(s)