Kelley’s Heroes

Posted on April 4, 2011 – 4:40 AM | by AdminBy William Burg

In March 1914, a ragtag army of thousands of migrant laborers arrived in Sacramento on their way to Washington DC to protest. Led by the charismatic “General” Charles T. Kelley, the marchers stirred fears of a reprise of the type of labor unrest that had resulted in the bloody 1894 Pullman Strike, when Southern Pacific strikers battled National Guard troops in the city’s railyards. Sacramento officials determined to make Sacramento the end of the road for “Kelley’s Army.”

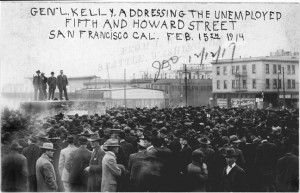

General” Charles T. Kelley addresses his army in San Francisco, February 1914 (Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.)

Then, as now, large corporate farms dominated California agriculture. Enormous numbers of migrant laborers worked furiously during the harvest season only to be unemployed during the winter months, living off their savings in the cities. In the winter of 1913, during a severe economic recession, Charles T. Kelley organized a group of unemployed workers in San Francisco. Inspired by his experiences as a member of “Coxey’s Army,” an 1894 march of migrant workers on Washing ton DC, Kelley planned to start another march on Washington to make their case to President Woodrow Wilson. Based in a two-story hotel near San Francisco’s city hall, “General” Kelley gathered at least 1200 men, while a second band of about 500 men, led by a “Major” Thorne, planned their own march on the same route, both departing on March 3, 1914.

City police departments in Oakland escorted the army to the Emeryville city limits, where they stayed one day before Berkeley police escorted them northeastward to Richmond. Contra Costa County was so eager to avoid having the army march through that they paid the army’s railroad fare to Sacramento.

Sacramento’s leaders had no use for Kelley or his army; only the summer before, striking hop pickers in nearby Wheatland had clashed with business owners and vigilantes in an incident known as the Wheatland Hop Riots . The riots resulted in four deaths and a hundred arrests. With Wheatland so recent, Sacramento feared civil disorder on the scale of the Pullman Strike, which had completely paralyzed the city 20 years earlier. The City Commissioners decided to isolate Kelley’s Army from the rest of the city while the governor decided how to deal with them.

This vacant lot at 3rd and I Street, became the encampment of nearly 2000 unemployed migrant workers known as “Kelley’s Army.” Today it's the site of the Amtrak passenger depot. (Center for Sacramento History)

Upon their arrival in Sacramento, both armies were escorted to a vacant lot along I Street, previously the site of China Slough and currently the site of the Sacramento Valley Amtrak passenger depot. The lot was bounded by a high wooden fence and guarded by 50 Sacramento police officers. The city provided shovels for digging privies and fresh water, while Sacramento County appealed to local charities to provide food for the army. Curious Sacramentans visited the encampment, treating it like a carnival had arrived in town. Members of the army sold postcards and engaged in music, sports and gambling to pass the time.

The Sacramento Bee was critical of the army, claiming that Kelley’s real plan was to seize government armories in Chicago, take Washington by force and dispose of President Wilson and Congress, and lead a nationwide workers’ revolt. Despite “Major” Thorne’s claimed affiliation with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the Sacramento IWW chapter refused to support Kelley’s efforts. 300 militiamen were called out to guard Sacramento’s armory, and nearby cities mobilized their own National Guard units. The City Commissioners and County Supervisors decided that Kelley’s Army should not be permitted to travel east of Sacramento, and asked Governor Johnson to provide them with barges to ship them back to San Francisco, and National Guard troops to help carry out the order. Kelley’s respondedthat he would leave in one week for Ogden, Utah if left alone, but would not return willingly to San Francisco.

Governor Hiram Johnson had little sympathy for migrant laborers. Sacramento Valley farmers were an important supporter of his campaign to limit the power of Southern Pacific in California politics, and he could not afford to alienate them. On March 7, he offered to find work for the strikers, which was refused by Kelley, who insisted that the army would accept no employment until they completed the march to Washington. Johnson’s response was to authorize trains to carry the army back to San Francisco on March 9 at 10 AM.

On the morning of the 9th, Kelley and his army defiantly refused to board the trains. 150 police and firemen stepped into action, arrested Kelley and 18 other leaders, and forced the army from their encampment onto Second Street. Using fire hoses and clubs, police pushed the army towards the M Street and I Street railroad bridges. A street melee broke out, wrecking three streetcars and the Bay Saloon on Front Street. Despite the chaos, there were no fatalities or serious injuries reported, and Kelley’s army soon found themselves on the Yolo County side of the river. Armed guards were posted on the bridges to prevent the army’s return.

As Yolo County officials tried to decide what to do about the situation, the army disbanded, breaking camp after most of those arrested (except Kelley) were released from jail on March 17. Cold, leaderless and without support, the army dissolved. A few members pooled $70 for a down payment on a lot in Oakridge Acres, an exclusive new suburban development near North Sacramento, and arrived there with 150 unemployed migrant workers. The county refused the sale and returned their deposit. General Kelley was sentenced to six months in jail for vagrancy. Major Thorne slipped out of town, escaping arrest.

The Army of the Unemployed, like the Pullman strike 20 years earlier, was one of several important labor clashes that came to a stop in Sacramento, like levees holding back a flood. 20 years later, this story was played out again, when cannery and agricultural workers were arrested in raids on Sacramento union headquarters, resulting in the 1935 Criminal Syndicalism trials (Midtown Monthly, December 2009.)

Kelley’s Army may have failed in their attempt to reach Washington DC, but their effort was not entirely in vain. Shortly after the dissolution of the Army, Gov. Johnson created the California Commission of Immigration and Housing to investigate the living and working conditions of itinerant laborers in California. That study led to the first detailed research into the lives of California’s migrant farm workers, and fed into the growing movement for worker’s rights.