Lucky Star: Clayton Bailey’s World of Wonders

Posted on January 8, 2012 – 1:32 AM | by AdminBy Tim Foster

Thank Robert Arneson.

It was Arneson who invited an obscure Midwestern ceramicist to cover a few of his classes at UC Davis, thus introducing Clayton Bailey to northern California – just in time to take his place in art history.

Bailey’s brand of whimsical sculpture might have played OK in his Wisconsin homeland, but in the mid sixties, serious art was the order of the day pretty much everywhere but on the west coast. Minimalism was erupting from the studios of Carl Andre and Donald Judd. Rosenquist’s billboard eyecandy was giving way to Richard Estes’ photorealist streetscapes. Even Andy “I only eat candy” Warhol had turned to pictures of car wrecks and Kennedy’s assassination.

Bailey’s brand of whimsical sculpture might have played OK in his Wisconsin homeland, but in the mid sixties, serious art was the order of the day pretty much everywhere but on the west coast. Minimalism was erupting from the studios of Carl Andre and Donald Judd. Rosenquist’s billboard eyecandy was giving way to Richard Estes’ photorealist streetscapes. Even Andy “I only eat candy” Warhol had turned to pictures of car wrecks and Kennedy’s assassination.

Inject into this era one Clayton Bailey. Part practical joker, part science nerd and 100% pop culture nostalgic, Bailey did not fit the then-current Clement Greenberg mold for ‘Artist.’ Lucky then, that he landed in California’s Bay Area just as that region was emerging as the epicenter of multiple ribald art movements ranging from underground comic books to Funk Art. Suddenly, Bailey found himself surrounded by artists who – like him – took as much inspiration from the pages of Mad magazine as from Artforum.

World of Wonders, the Crocker’s whopping 180 piece retrospective of Bailey’s work offers the chance to follow forty years of the artist’s development… or, arrested development, as some of his critics (cheerfully quoted on Bailey’s website) might argue. But, you’ll have to hurry: the exhibit closes on January 15.

The California that Clayton Bailey first encountered in 1967 could hardly have been a better fit for an artist of his inclinations. UC Davis nourished kindred spirits like Arneson, David Gilhooly and Roy De Forest. Across the bay, Robert Crumb was pushing copies of Zap #0 out of a baby carriage on Haight Street, while Chip Lord and Doug Michels were gearing up to form Ant Farm, the absurdist art/architecture/performance collective. There was literally nowhere else on Earth better suited to ‘get’ Clayton Bailey.

At first, Bailey continued the simple funk-influenced ceramic novelties which had charmed Arneson: goofy creatures (“critters” in Bailey vernacular), brightly colored sexually-suggestive pots and other non-utilitarian ceramics. In 1968 he created Burping Bust with Jumping Hair, a precursor of many jumping, burping, farting and/or gurgling sculptures to come. A low fire ceramic bust of a sharp-toothed cartoon figure, Burping Bust is filled with water and wired to periodically emit a ‘belch’ and lift the bright green foliage ‘hair’ that tops the piece.

There was a major shift in 1971 when Bailey invented Dr. George Gladstone, a mythical scientific explorer/promoter whose ‘discoveries’ occupied Bailey’s energy for much of the next decade – and fill a correspondingly large part of the Crocker exhibit. Likely inspired by both the 1967 Bigfoot sighting filmed by Roger Patterson and Crumb’s 1971 Whiteman Meets Bigfoot comic strip, Dr. Gladstone burst on the scene with the 1971 ‘discovery’ of a complete Bigfoot skeleton in Bailey’s adopted town of Port Costa. Soon Gladstone began unearthing ‘Kaolithic fossils’ from the ‘Precredulous Era’ – fossils made of what Bailey called ‘thermally metamorphosed mud.’ Numerous related ‘discoveries’ – all meticulously documented – appeared throughout the seventies and many are collected in the Crocker show. In 1976 Bailey rented a storefront on Port Costa’s main street and opened the Wonders of the World Museum, a home for his growing collection of Gladstone specimens. For two years the Museum displayed Gladstone’s most noteworthy Kaolithic discoveries along with special ‘fossil testing’ equipment.

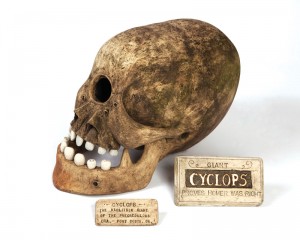

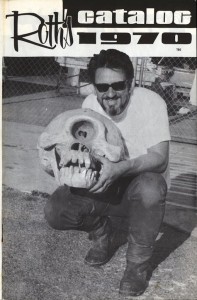

Part P.T. Barnum, part Roy Chapman Andrews, the Gladstone persona took Bailey’s work out of the realm of simple sculpture and added an absurdist conceptual dimension similar in conceit to the ersatz scientific projects Ant Farm had begun documenting during the same period – their time capsule burials, proposal for a ‘Dolphin Embassy’ and Media Burn performance at the Cow Palace were all couched as scientific explorations. And, certain aspects of the Gladstone mythology may have had an even more middle-class model: in his 1970 catalog, California hot rod/custom car designer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth prominently featured an oversized Cyclops skull (made by his then-assistant Robert Williams) eerily similar to the Giant Cyclops Skull ‘discovered’ by Gladstone in 1976. Bailey, a longtime hot rodder, was certainly aware of Roth, but whether he ever saw the earlier skull is unknown. If nothing else, the similarity underscores the B-movie/pop culture thread that marked the work of many California artists of the time

Part P.T. Barnum, part Roy Chapman Andrews, the Gladstone persona took Bailey’s work out of the realm of simple sculpture and added an absurdist conceptual dimension similar in conceit to the ersatz scientific projects Ant Farm had begun documenting during the same period – their time capsule burials, proposal for a ‘Dolphin Embassy’ and Media Burn performance at the Cow Palace were all couched as scientific explorations. And, certain aspects of the Gladstone mythology may have had an even more middle-class model: in his 1970 catalog, California hot rod/custom car designer Ed “Big Daddy” Roth prominently featured an oversized Cyclops skull (made by his then-assistant Robert Williams) eerily similar to the Giant Cyclops Skull ‘discovered’ by Gladstone in 1976. Bailey, a longtime hot rodder, was certainly aware of Roth, but whether he ever saw the earlier skull is unknown. If nothing else, the similarity underscores the B-movie/pop culture thread that marked the work of many California artists of the time

If Big Daddy Roth’s aesthetic was exactly one pubic hair away from Mad magazine, Bailey’s art exists somewhere in the wide margin between Roth and the edge-pushing LA sculptor Ed Kienholz. Both Bailey and Kienholz made noisy, electric-powered sculptures laden with references to pop culture, but the similarity ends there. Where Kienholz created intensely disturbing installations that can fairly be described as haunting, Bailey made sculptures that were fun.

That’s not to say that he never approached controversial subjects. Sex is a near-constant, from his early sixties Nite Pots to the 1972 Bigfoot Comparative Anatomy to his recent To Keep a Faithful Man cups. And, I was thoroughly fascinated by the display of his Surrogate Babies – a series of well over a dozen creepy fetus sculptures. There’s a clear abortion reference, but good luck figuring out if there is supposed to be a pro-life or pro-choice message. That level of ambiguity on a subject as charged as abortion is a masterpiece of subtlety.

That’s not to say that he never approached controversial subjects. Sex is a near-constant, from his early sixties Nite Pots to the 1972 Bigfoot Comparative Anatomy to his recent To Keep a Faithful Man cups. And, I was thoroughly fascinated by the display of his Surrogate Babies – a series of well over a dozen creepy fetus sculptures. There’s a clear abortion reference, but good luck figuring out if there is supposed to be a pro-life or pro-choice message. That level of ambiguity on a subject as charged as abortion is a masterpiece of subtlety.

Less successful are Bailey’s robot and raygun sculptures, most of which were made in the late seventies and after. While the craftsmanship is beautiful, I found these to be the least compelling works in the show. Where the Kaolithic sculptures have a sort of manic absurdity to them, the rayguns seem simply decorative.

Like most Funk artists, Bailey willfully blurred the line between art and craft. Unlike most, he benefited as the art world shifted in his direction. His appropriation of ‘Cabinet of Curiosities’ type imagery presaged the full-blown obsession that lowbrow artists (fueled by Robert Williams’ Juxtapoz magazine) would run with a generation later. At its best, Bailey’s work lives up to the show’s title, yet, for all its robots, rayguns, brains in a jar, aliens, mad scientists and other sci-fi twists, World of Wonders functions as a time machine in reverse. Instead of launching forward, the show is a trip backwards in time – back to nineteen seventy-something NorCal, and deep into the curious mind of a Midwestern boy who got to California just in time.

Clayton Bailey’s World of Wonders runs through January 15

Crocker Art Museum, 216 O Street

Tags: Art Review, Clayton Bailey, Crocker Art Museum, Dr. George Gladstone, Ed Big Daddy Roth, funk art, Robert Arneson, World of Wonders